Women Faculty

FAU's women faculty members have played a pivotal role in expanding the growth of various departments of education on campus. This project explores the marginalization and discrimination of faculty amid their constant dedication to the university’s growth and expansion. Studying the history of gender faculty protest at FAU in the 1980s through 1988 demonstrates how FAU failed to implement its own policies, avoided accountability, and did not represent women’s contributions in the history of FAU.

Let's begin with the discrimination that many women faculty members endured at FAU. The first few sources are newspaper articles from the Atlantic Sun, Florida Atlantic University’s student newspaper. The article titled “FAU Formally Cited For Sex Discrimination" on April 23, 1980, explains that the United Faculty of Florida (UFF) filed a major class-action grievance against FAU for discrimination against women in faculty and professional positions (FAU Formally Cited For Sex Discrimination 1980). The grievance was filed by a UFF grievance representative named Thomas F. Baxley, who was part of FAU’s philosophy department. It contained forty-one signatures of both men and women on the faculty who could cite evidence of discrimination. The statement claims that FAU was guilty "in its failure to put into effect the affirmative action guidelines regarding women mandated by the federal government” and that “The underutilization and chronic discouragement of women have resulted in a deterioration of the workplace from which all faculty, in different ways and degrees, suffer. The concern for gender inequality on campus was not an isolated situation, and many individuals, male or female, were affected and in support of the cause. FAU’s affirmative action policy coincides with the federal laws that prohibit discrimination. According to the article Equal Employment Opportunity: A Study Of Eeo In Five Selected Manufacturing Companies, there are major federal laws that prohibit discrimination in employment or provide equal employment opportunities (Bennett 1974, 9-10). The laws that apply in this case are Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, amended by the Equal Employment Act of 1972, and the Equal Pay Act of 1963. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 forbids discrimination in employment on the basis of race, color, religion, sex, and national origin. The Equal Pay Act of 1963 states that individuals must be paid equally, regardless of sex, if they perform equal work. The affirmative action regulations policy at FAU, which was adopted by the Board of Regents on December 8, 1974, was robust in its explicit procedures and handling of situations. According to the Personnel and Compensation Committee, “The State University System believes in equal opportunity practices which conform to both the spirit and the letter of all laws against discrimination and is committed to non-discrimination because of race, creed, color, sex, or national origin” (Florida Atlantic University 2012, 2). The policy then broke down the role of the president, university provost, and vice president as primarily responsible for carrying out the policy. It also provided a guideline for faculty and administrative actions based on certain criteria and what to do when a position becomes vacant. Considering the policy was very clear and does not leave much room for speculation, one could argue that the issue lies in the institutional practice rather than the policy itself. This reflects the structure of the administration and its priorities. Women could follow a regulated procedure yet still be undermined.

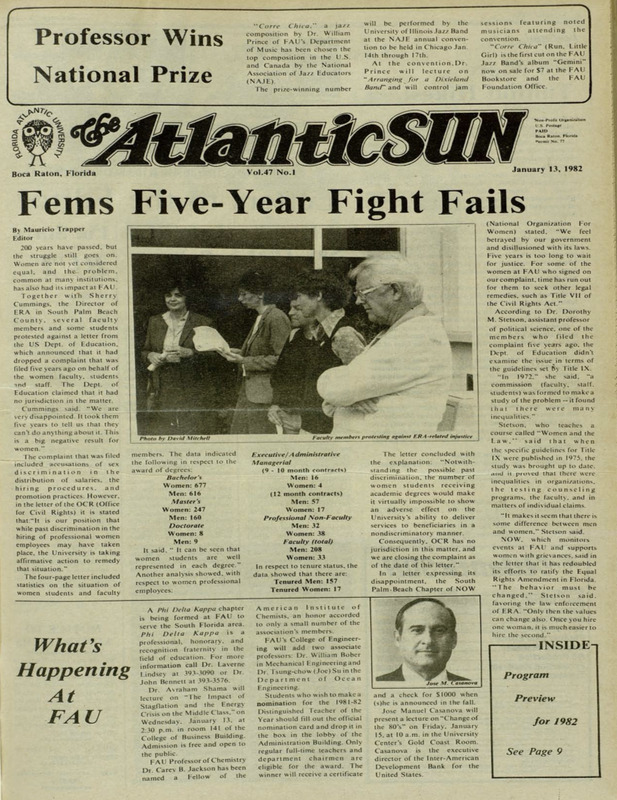

The newspaper article titled “Fems Five-Year Fight Fails,” dated January 13, 1982, demonstrates how federal authorities failed to assess the discrimination claims despite the evidence provided by faculty. The US Department of Education announced that it had dropped a complaint that was filed five years ago on behalf of the women faculty, students, and staff. The Department of Education claimed that it had no jurisdiction in the matter. They acknowledged that discrimination against women may have occurred at FAU, but they assured that the university took affirmative action as a solution. Professor Dr. Dorothy E. McBride Stetson, assistant professor of political science, stated, “The Department of Education did not examine the issue in terms of the guidelines set by Title IX… In 1972, a commission was formed to make a study of the problem- it found that there were many inequalities.” (Fems Five-Year Fight Fails 1982). The university's response included a set of statistics comparing men and women who were awarded degrees, executive and administrative managerial positions, and those who were professional non-faculty, faculty, and tenured. Men were awarded 616 bachelor's degrees, compared to 677 for women. 160 master’s degrees were awarded to men, while women received 247. 9 doctorate degrees to men and 8 for women. For executive roles, nine-to-ten-month contracts were given to 16 men and 4 women. 12-month contracts were given to 57 men and 17 women. The professional non-faculty had 32 men and 38 women. The faculty total was 208 men and 33 women. Tenured were 157 men and 17 women (Fems Five-Year Fight Fails 1982). These statistics show that women are getting educated, yet when they enter the workforce, there is still a glass ceiling. Of the 174 total staff, only 10% of women were tenured. Here is another example of women being underrepresented and undermined. The Department of Education’s suggestion that discrimination might have happened in the past, and referencing the university’s affirmative action policy, undermines the actual issue of discrimination and is a strategy to avoid accountability altogether.

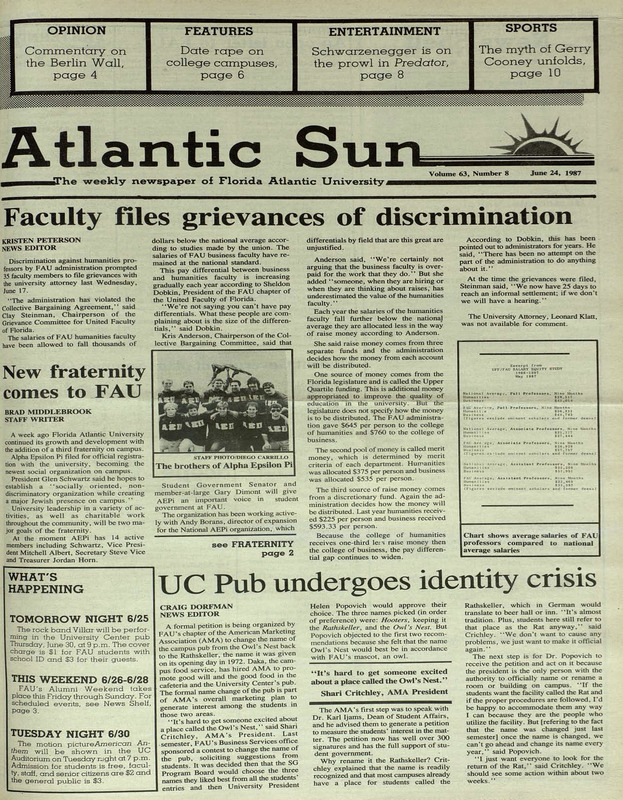

The newspaper article titled "Faculty Files Grievances of Discrimination," which was published on June 24, 1987, examines the discrimination that humanities professors faced because the field is heavily dominated by women. According to a Sun Sentinel article, “Thirty-five Humanities professors filed grievances on Wednesday with Florida Atlantic University, saying their salaries are low because of the “comparatively high number of women” teaching in their fields” (35 Professors File Sex Bias Claims on FAU Salaries 1987, 2). According to studies conducted by the union, FAU humanities faculty’s salaries had fallen thousands of dollars below the national average. This emphasizes the idea that male-dominated fields were valued more in comparison to women. This grievance reflects the issues from the 1980 and the 1982 articles showing that the discrimination had persisted over some years.

The article “Faculty Files Grievance Appeals,” dated October 21, 1987, emphasizes the continual fight by faculty and the administrative neglect. The grievance filed by thirty-nine humanities professors, male & female on the basis of sex discrimination and violations of academic freedom had been denied by FAU’s president, Helen Popovich. According to the newspaper, Popovich stated, “I directed Leonard Klatt to conduct a thorough study, and I am pleased that his investigation revealed no discrimination exists in the allocation of faculty salaries.” (Faculty files grievance appeals 1987). Klatt compared the salaries of FAU’s business faculty at institutions of higher status, including Ivy League institutions, to the humanities faculty. According to his study, the underpayment of the humanities faculty was no more severe than that of the business department. There is no evidence reporting that Klatt investigated differences in salary based on gender. However, a lot of the argument made by faculty was on the basis that the humanities department is made up mostly of women. So why did FAU’s first and only woman president deny the grievance? This poses the question of was Popovich’s decision in the best interest of the administration or the faculty? Was the decision based on a lack of funds? The primary responsibility for carrying out the affirmative action policy was in the hands of Popovich, along with the vice president and provost. One could argue that Popovich’s, the Vice President's, and the Provost's jobs were potentially being contested amid this tension. When contrasted with historian Donald Curl’s account, which emphasizes Popovich’s strides towards expanding opportunities for women, the newspapers show that her role was more complicated and controversial at the time of her presidency. In Florida Atlantic University Campus History, Donald Curl states, “Popovich used the position to work towards the hiring of more women and members of minority groups. She also supported women’s studies and saw the Women’s Studies Certificate program approved in 1986.” (Curl 2000). Contrasted with Curl, this grievance case serves as an example of how complex the issue of equal pay was not only for faculty, women, and humanities professors, but for the administration and the tension around it. The humanities faculty felt so strongly that they appealed their case, charging FAU administration with manipulating data and producing irrelevant or misleading studies (Faculty files grievance appeals 1987). These articles all have one thing in common, and that's the claims of FAU participating in some form of sexual discrimination during the same time period from 1980 to 1988, and the FAU Faculty advocating for better treatment. I cannot confirm whether the complaints made to the US Department of Education were organized by the same people who supported the grievance to the UFF, but nonetheless, these sources show the different avenues that individuals took to reach the same goal of demanding equal treatment for women and humanities faculty’s salaries, which sought to hold FAU accountable for discrimination.

Additionally, in Donald Curl's book, Florida Atlantic University Campus History, there is no mention of these women and their contributions to “campus history” or anything about gender equality protests. In a male-dominated environment, the perspectives and achievements of women were often overlooked or never documented at all. Curl’s representation of women contrasts with the primary sources, as women are depicted as more of a supporting role, like donors, while the primary sources depict women as actively advocating for change. In the article “We Are What We Keep; We Keep What We Are’: Archival Appraisal Past, Present and Future” the author states, “In many societies, certain classes, regions, ethnic groups, or races, women as a gender, and non-heterosexual people, have been de-legitimized by their relative or absolute exclusion from archives, and thus from history and mythology—sometimes unconsciously and carelessly, sometimes consciously and deliberately.” (Cook 2011, 2). Similarly, as a result, these biases are embedded in the preservation of FAU’s history. To better grasp the depth of these women’s fight for equality, it is important to highlight the lives of the faculty who protested discrimination at FAU. These women were huge contributors not only to protesting for equal rights but also to the intellectual life and institutional organization of the university. Professor Dr. Dorothy E. McBride Stetson was a Florida Atlantic University Professor Emeritus of Political Science (Florida Atlantic University 1990-2000, image faua0000928). She not only spoke out on the inequality but also was part of the faculty who signed a complaint to the Department of Education. Dr. McBride also served as a founding board member of the Center for Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies from 1985-1996. Dr. McBride’s contribution to FAU is huge as she expanded the teachings on women, gender, and sexuality while also challenging the systematic issues of discrimination by creating a space to have conversations about feminist theories and social justice. This movement was not only about promoting change in FAU but was also her life’s research work. Heather Frazer was a history professor who taught courses in women’s history, modern Britain, the British Empire, Indian history, and oral history from 1971 to 2006 (Florida Atlantic University, image faua0000913). She was part of a team of faculty and staff that lobbied for a Women's Studies curriculum. Frazer was a part of the movement on FAU advocating for women’s equality. The efforts made were not just in the grievances or complaints, but also in pushing the structure of the school and what is being taught. Frances Myers was a theater professor from 1969 to 2001 (Florida Atlantic University 1979, image faua0000924). In addition to teaching, she served as the president of FAU's chapter of the United Faculty of Florida. In a Sun Sentinel article, Frances stated, “We feel there is sexual discrimination. It’s based on existing salaries, but we have no idea what they will throw up as the criteria for proving it” (35 Professors File Sex Bias Claims on FAU Salaries 1987, 3). All these women were doing far more than just showing up to teach and then going home. They were participating in forms of activism, in leadership roles, and creating new academic programs. These women were laying the groundwork for the future voices of women on FAU’s campus.

To conclude, FAU’s affirmative action policy has since been amended on July 6, 2012. The amended version is about half the length and is vague in the handling of cases. There is no information on guidelines, the faculty, or the role the president has in affirmative action at the university. This leads to how this potentially affects the growing university in how it handles discrimination cases. What does this mean for the future of representing women equally at Fau? The affirmative action policy is often debated in state and national news, which makes the history of affirmative action all the more important. The exploration of the marginalization and discrimination of women faculty allows for a better understanding of why it is important to highlight these women. While being undermined, underrepresented, and underacknowledged, these women sought to change the structure of FAU while expanding educational programs and being professors. However, these women were more than just academics; above all, they were activists, leaders, trailblazers, and resilient