Mexican Colonial Churches

As part of her work with the State Department, Arquin developed an educational series of slides on Colonial Architecture in Mexico, complete with a script. She encourages those who use the slides and her script to make frequent use of maps to help their students understand the geography of the churches and Mexico at the same time.

Arquin is frankly celebratory of colonialism in Latin America. In her introductory remarks, Arquin highlights the “great task” before missionaries who arrived in Mexico of converting the native populations and how so much of that conversion depended on art and architecture. Arquin also points out that the missionaries arrived on shores that had “a very high culture already existing.” Arquin credits native artisans with the expertise to both execute missionaries’ designs, but also to offer design input of their own, culminating in the Churrigueresque style.

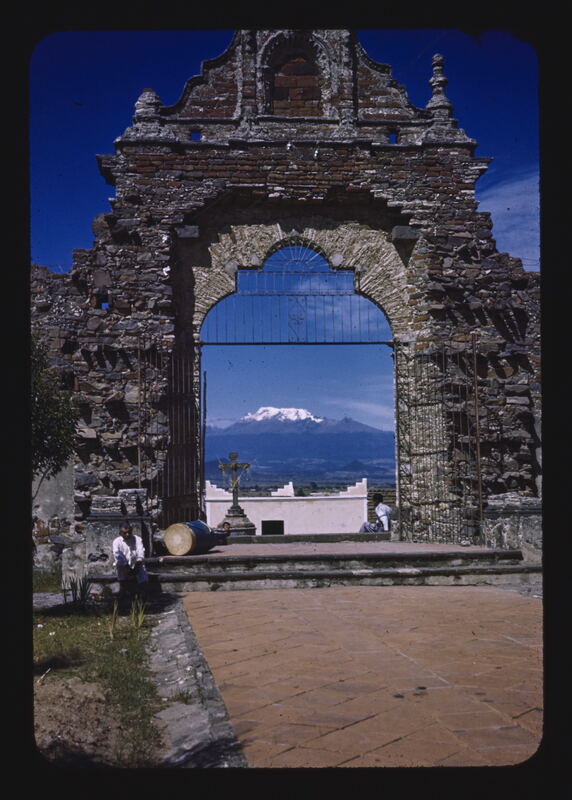

Arquin clearly thought that her photography was an important contribution, as she highlighted these images in interviews. She even indicated that some of the churches she photographed no longer stood or had been damaged in the intervening years.

What follows below are a selection of the 81 slides she originally intended for the presentation. They generally follow a chronological order from 1525 through the 18th century. Together with the slides, we have also provided some of the commentary Arquin meant to accompany the images, as well as information from our own research. Readers will notice that Arquin’s commentary is focused on formal characteristics of the various styles of colonial architecture.