Owls Rise: FAU's Earliest Forms of Protest and Activism

Since the inauguration of Florida Atlantic University in 1964, students have freely shared their thoughts and opinions with the intention of improving their local community and society at large. Protests and various other forms of activism, such as panels, lectures, and petitions, helped to inspire students to engage with discourse, giving them a sense of participation and forming a caring campus culture. This page of the Owls Rise: FAU Histories of Activism and Protests discusses some of FAU’s earliest forms of protesting and activism throughout the school’s first ten years. To this end, sources from the school’s student-led newspaper, The Atlantic Sun, will be investigated, as it has been capturing the students’ perspectives on these events since it started printing in 1966. During the 1960s and 1970s, United States’ citizens faced some of the nation’s greatest political and societal issues, leading to events such as civil rights movements and the rise of environmentalism. By relying on protests and activism, citizens risked their personal safety to more convincingly articulate their grievances and advocate for those in power to address their misgivings. Similarly, societal issues were experienced on campus at FAU, as students encountered events such as misappropriations of school resources, restrictions on campus activities, and local recognition of civil injustices. Although articles pertaining to students’ political involvement at FAU are scarce, these four sources show that FAU has a history of social activism from its inception. These sources depict the value students have always placed on campus community, especially at FAU.

According to the Atlantic Sun article "Peace Members at FAU 'Doves' To Protest Vietnam War,” in 1967, FAU’s protest against the Vietnam War was the university's first occurrence of the staff and students coming together to protest an issue they had unilaterally valued (Abels et al., 1). The singular event is the first recorded protest since the start of FAU’s newspaper the Atlantic Sun in 1966. The staff and student body recognized that the school was established enough to be able to house a protest that spoke to the nation as a whole. According to the article, the protest was co-sponsored by the United Campus ministries and endorsed by campus staff and faculty (Abels et al., 1). The unilateral purpose of the protest was to display the university’s anti-violence stance. With the mobilization of such a large community, they made it evident that their voices would not be ignored. According to Dr. Donald Curl’s book, Florida Atlantic University: Campus History, FAU had won a water ski championship, been endowed the Alexander D. Henderson University School, and was rated “Superior” for the Readers’ Theatre competition by 1967; providing the school with some social capital and establishing itself as a notable university within Florida (Curl 67-70). According to the article, various religious groups and clubs came together to protest the United States involvement in Vietnam. The Vietnam War was a large-scale issue that had no direct tie to the University, but the students and various clubs and organizations found the national conflict to be important enough to publicly protest against it. The protest was a display of the strength of unity within a community, in this case FAU’s community.

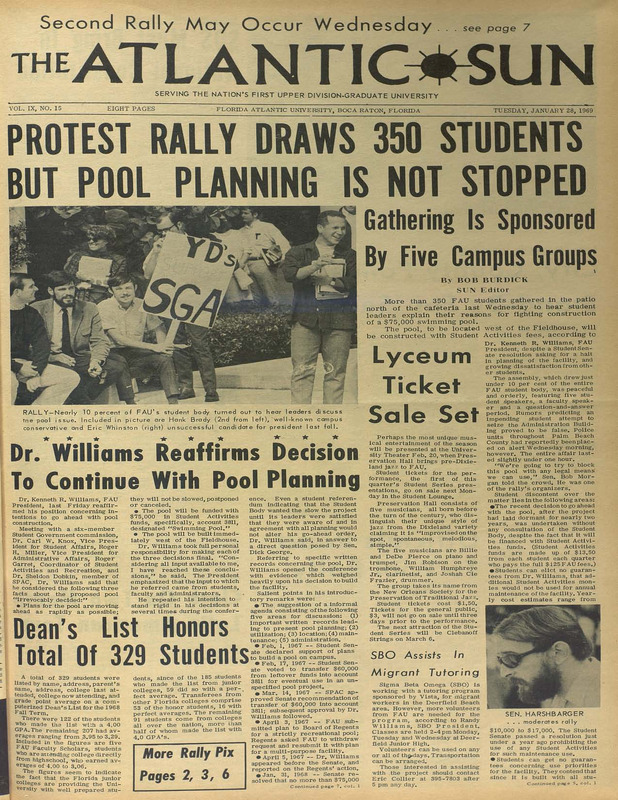

FAU’s second recorded protest in the Atlantic Sun occurred in 1969. A group of over 350 students came together against the building of a campus pool in FAU’s Boca Raton campus due to the high cost of $75,000. According to the Atlantic Sun article, "Protest Rally Draws 350 Students but Pool Planning Is Not Stopped," students believed the money would be better allocated to go towards student activities and the student body. Due to the school still being relatively new, the students believed the funds could help bolster the community engagement of students (Burdick, 1). This protest is an example of the FAU’s student body attempting to enact change within their local community. The building of the pool directly affected the student experience at the university as the allocation of the funds to the pool meant less ability to impact the culture on campus through student activities. Although the student body did not succeed in halting the building of the pool, as it was later installed and remains today; this protest recognizes how the students of FAU recognized an issue within their community and attempted to make a change. In recent years, the students of FAU have utilized their free speech through petitions to attempt to prevent the construction of buildings. In 2025, Sephora Charles’ article, “FAU’s Burrowing Owl Relocation Sparks Student Backlash and Concern”, from FAU’s most recent newspaper, University Press (UPress) discusses the more recent issue of FAU building dorms on the burrowing owl (the school’s mascot) habitat (Charles, 1). FAU students continue to freely share their opinion, especially on matters they deem important and work together in attempt to achieve their goals.

Although panels may not seem as aggressive as a form of activism, they are beneficial as they educate many on a topic that is frequently underutilized or typically not included in one’s standard education at the time. In 1970, FAU hosted three panelists to discuss gender equality, including Dr. Susan B. Anthony (the grandniece of the suffragette), Doria Yeaman, and Roxy Bolton. According to the Atlantic Sun article, “What do Women Want? Panel Says Constitutional Equity,” the panel was held on December 1st and discussed the importance of education for women, women’s mental health, and to demand maternity leave once in a career. According to the article, the event was planned due to FAU’s desire for community and understanding of diverse backgrounds after the big push for equality after the civil right movement. While there is no further discussion on whether the panel was one of a series or a particular special event, the attendees appeared to be inspired and influenced by the panel (Huszar, 1-6). The panel was open to students and the local community but heavily discussed the importance of the education of women. Afterward, attendees were allowed to ask questions and meet with the panelists. This panel provides an example of activism in a format that educates and amplifies voices that may not typically be heard under other circumstances. In more recent history, FAU continues to amplify voices through panels, exhibits, and symposiums such as FAU’s 2024 panel entitled “Political Circus,” which was reported on by Sage West in FAU’s current newspaper, University Press as a place for civil discussion that “[A]ims to spark dialogue and critical reflection on American politics and culture”(West, 1). FAU has also displayed their interest in providing inclusion for diverse communities with their 2025 exhibition “A Century of Jews in Boca Raton (1925-2025)”, which recognizes a community that has faced prejudice throughout history. Unlike the protests depicted in the other examples of FAU’s early activism, this panel was purposefully meant to educate and provide a sense of peaceful community for the students. Although FAU now provides courses on the topic of Women Studies, at the time, there was little to no access for students to learn more about the topic outside of the optional panel.

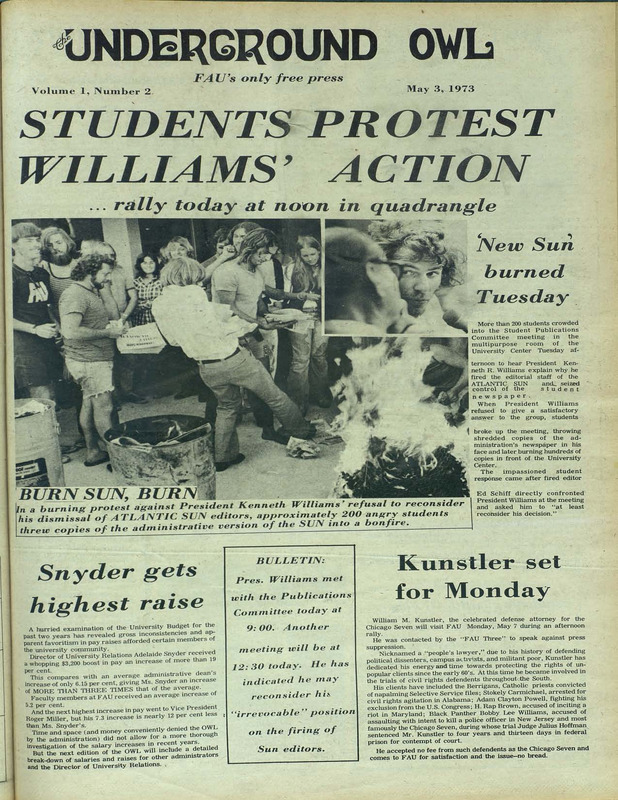

By 1973, FAU’s The Atlantic Sun had become a well-established newspaper on campus. The Atlantic Sun had been providing students with news for seven years. According to the Underground Owl article, "Students Protest Williams' Actions," in May of 1973, Dr. Kenneth William’s FAU’s first president, had dismissed the editors of The Atlantic Sun and replaced that staff with members of FAU’s administration. At the time of this article’s release, the students had come to an agreement that Williams' failed to provide a satisfactory reason as to why the firings occurred (Williams, 1). This inability to provide a direct response as to why the students were removed by the student-led newspaper can be viewed as a form of silencing free speech. This led to the students previously running the newspaper to protest the “new” Atlantic Sun and released the first edition of The Undercover Owl, a student-controlled newspaper. According to the article, Williams became the editor of the “new” Atlantic Sun which led to further animosity between the university’s president and the students at the university. In addition to the creation of the Underground Owl, FAU 200 students including students that were not involved with the newspaper protested of the administrative run of the Atlantic Sun, by burned the most recent edition of the newspaper on campus. This protest is an example of FAU students making their voices be undeniably heard by FAU’s administration through the intrepidness of their actions (Williams, 1). The burning of the “new” Atlantic Sun demonstrated that similarly to previous protests held by the students of FAU, the students have recognized and utilized their ability to use free speech and how when students recognized an issue larger than themselves, they were willing to come together as a community and make changes. The protest showcased unity between those directly effected by an issue, the students of the newspaper, and various students uninvolved with the newspaper's shared interest in fixing an issue they all viewed as wrong. Like FAU’s 1969 pool protest, the students recognized a flaw with how their university was running and made their stance evident through public means.

The sources presented unequivocally show that FAU has had a history of political activism since its inception. These sources depict the value students have always placed on campus community especially at FAU. FAU’s anti-violence Vietnam war protest, their first protest against the construction of the campus pool, their first women’s liberation panel, and the protest against campus administration’s hold on the Atlantic Sun frame the university’s student body as empathetic and engaged citizens. While many universities are politically active, what separates FAU from the universities across the nation is the unique and diverse community these protests created and continue to foster in modern forms of protests and activism. This project allows us to see the commonalities between past activist events and today’s campus culture. This insight is the reason why history is taught and can help inform us of what the future will hold for tomorrow’s Owls.